Cormorants

Cormorants. Those oily, croaking, snakey birds that hang out on rocks, steal fish and kill vegetation with their excrement. This delightful set of attributes put me off cormorants until an excellent field trip with the Santa Clara Valley Bird Alliance. Watching cormorants whiz by over the waves and identifying them on the ocean instilled a sense of wonder and excitement that I hadn’t felt for them before. This article is my olive branch to the cormorants for ignoring them for as long as I did!

Cormorants, or Shags as they are sometimes known, are the common name for the wider family Phalacrocoracidae that contains over 40 different species worldwide. In the US, we can cut that number down to 6, and being more specific to the Bay Area to 3 (omitting the elusive Neotropic Cormorant that is threatening to show up). Cormorants are diving birds that spend a significant amount of their time in bodies of water hunting for prey. These non-Passerines have numerous adaptations to aid this. Their webbed feet placed far back on their bodies propel them through the water in a streamlined shape - handy for exploring underwater. To aid in getting below the waters surface they reduce their buoyancy by wetting their feathers. This wettabillity results from under-developed oil glands that only partially oil a cormorants feathers. To keep their feathers in good condition, cormorants spread their wings out in the Sun or wind to dry off. Evolutionary wise our 3 cormorants diverged ~10-20 million years ago, and are 40 million years further separated from the anhinga, a very similar looking bird. Convergent evolution in the cormorants has resulted in all 3 of our species appearing quite similar to each other. Confounding this for us is the fact that the range of these cormorants in the Bay Area greatly overlap. However, these 3 are distinct in many interesting ways.

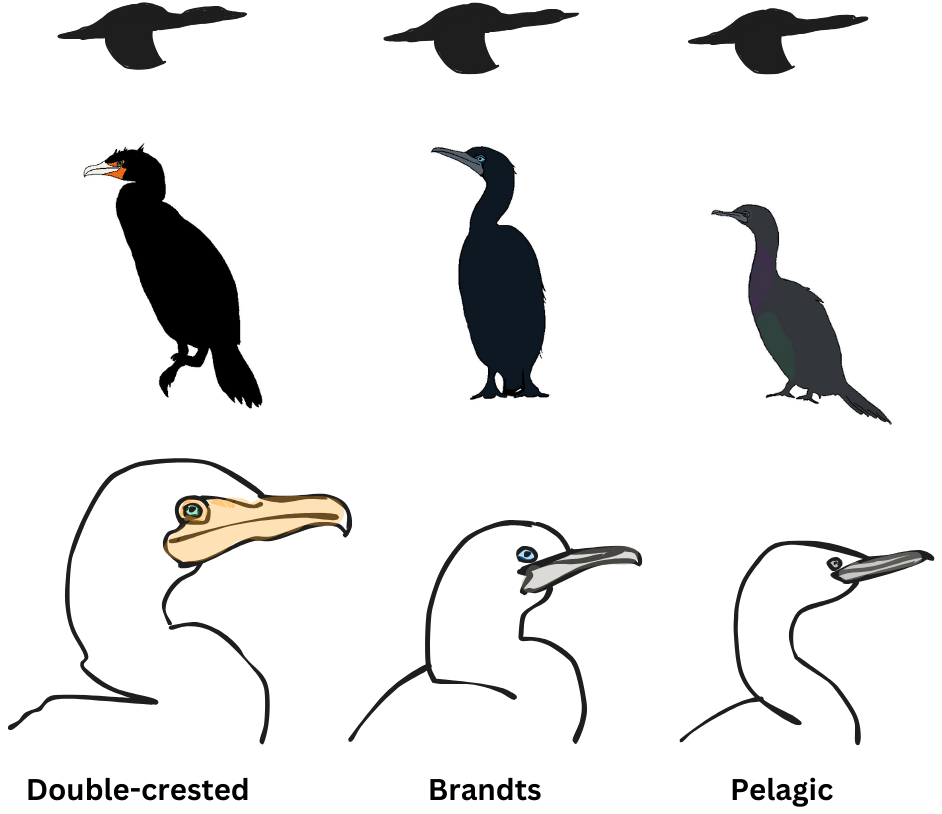

The 3 cormorants we have in the Bay Area are the Double-crested Cormorant, Brandt’s Cormorant and the Pelagic Cormorant. A cartoon diagram is shown below to highlight their main physical differences. Size wise there is a rank ordering - the Pelagic is noticeably smaller, whilst the Double-crested and Brandts are larger and roughly equivalent sized birds. Beak shape is another good delineator of cormorants. Double-crested has a thick, robust bill, the Pelagic has an almost delicate, pencil thin bill and Brandts somewhere in between. While the dominant feather hues are blacks, greys and browns, we can find distinct coloration on our cormorants. This is most obvious on the Double-crested, with its smattering of orange by the eye (the lores) and beak (the gular pouch). This orange is absent in the Brandts and Pelagic. Brandts is distinguished by an all black appearance until breeding season, when brilliant blues show up on their faces. The Pelagic’s feathers often dazzle by the sparkling green and magenta hues in a perching bird. Facial differences exist too, with the eye position and size relative to the beak appearing to give the Pelagic a more scrunched up, forward face.

It would be hard to use eye position as a field marker (especially for distant flying birds) but luckily we can identify these cormorants from miles away by looking at their postures when in flight. The way each of these three cormorants hold their necks and head when in flight is distinct, and surprisingly noticeable even at reasonably long distances. The Double-crested holds its head in a kinked, S-shape formation which really emphasizes the thickness of it’s neck. The Brandts and Pelagic cormorants hold their heads straight in line with their necks, but neck thickness to head size is very different between the two. The Brandts looks somewhat paint brush like in flight, with head being slightly bigger than the width of the neck, whilst the Pelagic in flight presents a solid line through neck and head!

Behavioral differences between the cormorants can also give us clues when observing at a distance. Both Brandts and Pelagic are birds of the ocean, being almost exclusively found on the coastlines. Double-crested on the overhand is found on the coast and in-land on fresh water ponds. Spying a cormorant in a fresh water pond likely means it’s a Double-crested. In fact, the Double-crested is found throughout the interior of the US! Socially, the Brandts cormorants often fly together close to the oceans surface, unlike the Pelagic or Double-crested.

A mix of diving, swimming and flying makes cormorants pretty energetically expensive, with one study estimating they burn 2500 calories a day, the same burn rate as us but with only 2kg mass! Fueling themselves is therefore of great importance to cormorants, and is a fascinating section in cormorant behavior. All three cormorants can co-exist in the same area, however the exact niche they feed in is distinct. Cormorants have a wide and varied diet, with some surveys estimating Double-crested’s eat up to 250 different species of fish, this plasticity in diet must help our feathered friends peacefully coexist. A study of these behaviors on the West coast of the US (see reference below) found that Pelagic Cormorants prefer feeding on solitary prey in rocky terrain near the shoreline such as Sculpin and Rockfish. Despite their name, Pelagic's aren’t often found feeding out in the open ocean. The Double-crested when feeding in the ocean prefers schooling fish in the mid to upper water column. Brandts hunt prey in a mix of rocky terrain and the sandy ocean floor. Even more interesting than this is that in Southern California where the Pelagic’s range ends, Brandts move to feed in the vacant rocky habitat. A cartoon summary of this complete picture is shown in the figure below.

Now we get to the excrement part…just kidding. I’m converted to appreciating cormorants thanks to their fascinating feeding habits. For all their ubiquity and somewhat plain appearance, I missed a key aspect of birding: the subtle behavioral differences that gives each species personality. The Cormorants are a good example of that. Now when I’m out by the coastline I look very carefully for these birds as they fly and dive. I even exclaim a little when a Brandts goes whizzing by.

Appendix

Interesting scientific articles on Cormorants include:

Mason R. Stothart et al., “Counting Calories in Cormorants: Dynamic Body Acceleration Predicts Daily Energy Expenditure Measured in Pelagic Cormorants,” Journal of Experimental Biology, January 1, 2016, jeb.130526, https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.130526.

Martyn Kennedy and Hamish G. Spencer, “Classification of the Cormorants of the World,” Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 79 (October 2014): 249–57, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2014.06.020.

David G. Ainley, Daniel W. Anderson, and Paul R. Kelly, “Feeding Ecology of Marine Cormorants in Southwestern North America,” The Condor 83, no. 2 (May 1981): 120–31, https://doi.org/10.2307/1367418.

James Walter Scholten, “Behavioral Variarions of Brandt’s Cormorants (Phalacrocorax Penicillatus)” (Master of Science, San Jose, CA, USA, San Jose State University, 1999), https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.euns-5h3s.